A customer who had migrated from Oracle to PostgreSQL several years ago recently reported a serious performance regression. A critical table—now holding over 700 million rows—had become extremely slow when filtering by date.

As an DBA, I approached this from an Oracle perspective: partition pruning, local indexes.

PostgreSQL partitioning is broadly similar to Oracle’s, but there are several important differences that often surprise Oracle DBAs. This case highlights one of the most impactful ones.

1. Original Table Definition (Non-Partitioned)

The original table in PostgreSQL was created without partitioning:

CREATE TABLE sales_no_part(

id INT,

hostname text,

sale_date date,

CONSTRAINT sale_pk PRIMARY KEY (id)

);

create index ind_sales_no_part_hostname on sales_no_part (hostname);

With hundreds of millions of rows and frequent date-based queries, this design forced PostgreSQL to scan a massive amount of data.

2. Partitioned Table Definition

To take advantage of partition pruning, I recreated the structure using range partitions:

CREATE TABLE sales (

id INT,

hostname text,

sale_date date,

CONSTRAINT sale_pk1 PRIMARY KEY (id, sale_date)

) PARTITION BY RANGE (sale_date);

create index ind_sales_hostname on sales (hostname);

Notice that the primary key includes the partition key.

This is a key difference compared with Oracle (explained later).

3. Performance Comparison

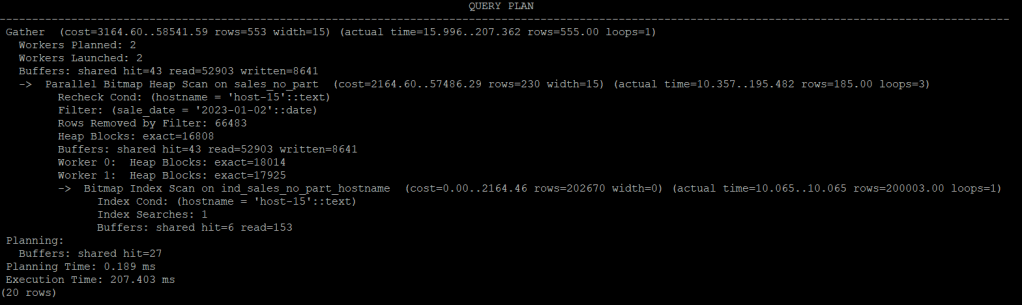

- 3.1 Non-Partitioned Table Query Performance

EXPLAIN ANALYSE

SELECT * FROM sales_no_part WHERE sale_date = '2023-01-02' and hostname='host-15' ;

Result:

The Execution Time: 207.403 ms

A massive Bitmap Index Scan—exactly what you would expect from a 10M-row heap table with an index.

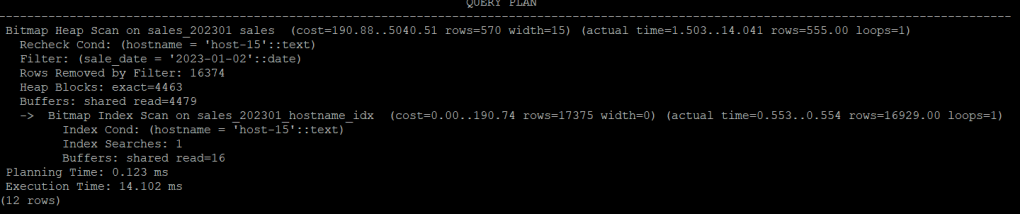

4. Partitioned Table Performance

Let’s compare the query on the partitioned version.

EXPLAIN ANALYSE

SELECT * FROM sales WHERE sale_date = '2023-01-02' and hostname='host-15' ;

Execution Time: 14.102 ms Before creating any index on the partition, PostgreSQL still performs a Bitmap Index Scan in only one partition,. The performance is 14 times faster than a table non-paritition .

5. Key Differences Between Oracle and PostgreSQL That Matter

As Oracle DBAs, we expect certain partitioning behaviors. PostgreSQL behaves differently in a few important ways.

- Difference 1: Partition Key Must Be Part of the Primary Key

If you define a primary key without the partition key:

PRIMARY KEY (id)

PostgreSQL raises:

ERROR: PRIMARY KEY constraint must include the partition key

Why?

Because PostgreSQL enforces global uniqueness across all partitions.

A partitioned table is treated as one logical table.

All partitions are physically separate tables.

PostgreSQL still must enforce the PRIMARY KEY as globally unique across all partitions.

- Difference 2: Local Index

In Oracle, you should use “LOCAL” to create local index, otherwise the GLOBAL index will be created.

CREATE INDEX ind_sale_date ON sales (sale_date) LOCAL;

Oracle automatically creates one local index per partition.

In PostgreSQL, the default index in partition is local index.

CREATE INDEX ind_sale_date ON sales (sale_date);

You can check child index .

SELECT indexrelid::regclass AS index_name

FROM pg_index

WHERE indrelid = 'sales_202303'::regclass;

index_name

---------------------------

sales_202303_pkey

sales_202303_hostname_idx

(2 rows)

the index sales_202303_hostname_idx was created automatically.

Or you can create each index manually, like this:

create index ind_sale_date_202303 on sales_202303 (sale_date);

create index ind_sale_date_202304 on sales_202304 (sale_date);

...

- Difference 3: Practical Partition Limits

Oracle officially lets you create up to 8,192 partitions, but honestly, you almost never see that in real life. From my experience, once you go beyond 1,000 partitions, things start to slow down and the database becomes harder to manage.

PostgreSQL doesn’t have a strict limit on how many partitions you can create. But in practice, when you get past roughly 100 partitions, you’ll start noticing performance getting worse because the planner has to deal with too many partitions.